The British Isles has large and diverse areas of clay that are suitable to make pottery. Broadly speaking, the area diagonally south of York and down to Cheshire has in various places clay deposits that are close to the surface. This enabled people from much, much earlier times and up to the Viking period to dig clay for pottery without having to go too deep. Clay is very heavy, and difficult to dig out. The rest of Britain by and large had to make do with 'costly' imports that could have come from a few miles down the road, or possibly several days travel away. Their only other alternatives were wooden vessels, or in other more remote areas, 'soft' soap-stone containers.

|

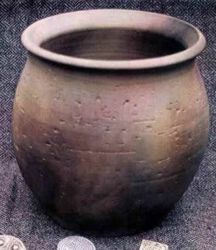

Pottery was a very important method of producing cheap cooking pots, bowls, cups, lamps, bottles, jugs, etc.. It was also used for loom-weights, crucibles and moulds. In early pagan Anglo-Saxon times pottery 'urns' were used to hold ashes of people who had died and been cremated. These were then often buried in small 'barrows'. Many of these cremation urns were highly decorated. The vast majority of the early pottery though was simply made, probably within the village or on the farm, using methods such as coiling or making thumb-pots. Later on, as shown by excavated examples, there were specialist potters who made wheel thrown pottery in towns. This was then sold by the potter, or possibly by travelling merchants in the markets, although some pottery would still be home produced.

|

Throughout the period pottery was also imported, especially from the Rhineland because of it's decorative nature. Pots that have survived show that ceramics of the period were often decorated by rouletting, thumbing, incising, combing, stamping or by applying clay to the surface. Sometimes the pottery was glazed with simple glazes, most often of yellow or olive green (the technique of glazing appears to have been reintroduced from the Byzantine countries through France). Other pottery was decorated with a red paint or slip in the continental style.

|

The pots were used for a variety of purposes, some for storage, some for cooking and some for eating and drinking from. Bowls would have been used for storage as well as cooking, eating and serving. Cups were generally in the form of handle-less beakers.

A potter's tools were fairly simple. An animal rib or flat piece of wood for shaping the pot when throwing, knives for trimming, antler tines for piercing for spouts and bungs, perhaps a number of sheep's tibiae and metapodials (elements of the bones in the foot of the animal), as templates for rim profiles. Some carved bone and antler stamps were used with rouletting wheels for decorating the pottery.

Evidence would suggest that after about 900AD the potter's wheel as we would recognise it came back into fashion. The type of potter's wheel probably varied, anything from a small turn-table (slow wheel) to a large kick wheel. Two kinds of fast wheel may have been used. The first and most likely type to have been used in the Saxon period, is basically a cartwheel mounted horizontally on a pivot, the wheel being rotated by hand or with a stick. The pot was thrown on a disc or small platform fixed to the centre or nave of the wheel. The other type consisted of a lower wheel turned with the foot and an upper wheel head for throwing the pot, the two wheels being connected by a series of struts.

To make clay good enough for a pot, the Saxon potter would have to put in some back-breaking graft. After unearthing a large amount of clay, he would take his raw material, steep it in water and then beat it, usually with a large wooden 'spatula' until it was well mixed, although some potters may have worked it by treading it with bare feet. He would then remove any large stones and gravel from it. Next, he would carefully mix sand, crushed shell, grass, or even crushed pottery from broken fired pots in with it to help bind it together. Then he would have to wage it (knead it like bread), to ensure it was thoroughly mixed. The clay at this point would have to be made pliant enough by the addition of water or be left to dry some more. The potter would then take a ball of this clay of the correct size and consistency for the item he was making. This clay was formed into a pot, mainly by building it up from layers of rings which are smoothed together by hand (coiling) or, by about 900AD, on a wheel. Other methods may have included paddle and anvil techniques, with a pebble and spatula, thumb pots and moulding over wooden moulds (this method was often used to make crucibles).

The item would then be left to dry gently. Features such as handles and spouts were usually added to the vessel when it had dried to a 'leather' hardness, or was firm enough not to distort when being handled. The simplest, and commonest, form of spout is the pinched spout made by pulling out the rim from inside with one finger whilst supporting the rim in position on the outside with two fingers. In this case this was done when the pot was first made. Tubular spouts were made either by throwing a small cylindrical shape, or by moulding clay around a forefinger, stick or bone. This was then smoothed onto the outside of the vessel once a hole had been made. Handles would be made by throwing, pulling or rolling out, and also applied by smoothing onto the outside of the pot. At this stage the bottom of the pot might be trimmed with a knife to give the familiar 'saggy bottom'. The 'saggy bottom' was we believe better for cooking with, as it helped to even out the differences of temperature in a cooking fire, which could easily crack a pot. Floors of the period weren't very flat themselves, so rounded bottom pots really didn't matter.

The container could then be worked over with a damp cloth or wet hands, which brings the finest clay particles to the surface, giving a smooth finish. The inside of the pot could also be burnished with a smooth pebble or bone to smear the clay particles over each other producing a more water tight vessel. It could also be decorated by painting with a slip (a creamy mixture of fine clay and water) of a different colour to the body. Sometimes slip painting amounted simply to vertical stripes of slip, sometimes it took the form of scrolls and swirls. Glazes were almost universally lead based, giving a greeny yellow colour, although copper or iron could be added to change the colour or add speckles of a different colour. These were added to the pot after an initial firing. The glaze could have been applied as a dry powder, although most was applied as a water based paste. Liquid glazes could be applied to the leather hard pot with a brush or by hand smearing, which accounts for the uneven thickness of many of the glazes from this period. The pot could also be dipped in a bath of glaze. It was then left to finally dry before it was fired to make it hard.

In the early period the pots were fired in a covered fire pit called a clamp. This did not always reach a very high temperature so the pots often did not fire very well. The fire that was built over the pots excluded most of the oxygen which fired the pottery black or charcoal-grey. By the later period firing was done in a simple kiln which was easier to control, guaranteeing a better and more even firing.

In order to make a kiln the potter dug two shallow pits, one of them with a semi-permanent wall of clay or stone (sometimes insulated with earth or turf) with a simple domed roof built over it, possibly just of turf, but sometimes of clay. (Turf is fine for a single firing, but if it becomes too roasted, breaks down into sand and minerals which just don't hold together). This one became the kiln and was joined to the other pit by a small opening. The pots were stacked in the kiln, generally upside-down, sometimes one inside another, whichever way they packed most tightly. The loading could be done through the top of the

|

The kiln was then sealed with wet clay leaving just the opening between the pits and a small flue opening. Some kilns had a raised central floor on which more pots were stacked, which allowed the hot air to circulate around the pots better. A hot fire was then built in the second pit in front of the opening. The potter would keep adding fuel slowly until the temperature was high enough to fire the pots, gauging its 'readiness' by the degree of luminosity of the items which glow whilst being fired. When this temperature had been reached the potter let the kiln cool down (sometimes for a whole day) until it was cool enough to remove the pots. Most would be hard and ready for use although some would have cracked if the clay and sand or shell had not been correctly mixed. With maintenance, a kiln of this type might last from five to ten years.

By the tenth century there were several major pottery centres in England which exported their wares throughout the country. These included Thetford, Stamford, Lincoln, Torksey, Stafford, St. Neots, Winchester and Ipswich.

Most of the pottery available in tenth and eleventh century Britain was of a buff, grey or pinky-orange colour. Red clay of the flowerpot terracotta type is almost completely unknown except for applied slip decoration. Glazes tended to be greeny-yellow, or rarely orangey-yellow and may have had speckles of dark brown, dark green or yellow. Some pots would have been almost black due to a process known as reduction. This happens when oxygen is excluded from the kiln by clamping off any airways, and leaving it for a period of time.

It is interesting to note that although pottery was widely made in Denmark and southern Sweden, in Norway it was very rare, usually only being found as imported wares. Most cooking pots were made from soapstone - this is due to the fact that in Norway's rocky terrain, the easily carved soapstone is quite common, but clay deposits are quite rare.

|

|

|

|

|

The types listed above are some of the main types of English pottery in our period. However, hand-made pottery was still being produced locally and good quality pottery was being imported from the continent. No doubt, foreign pottery was used to demonstrate an individuals cosmopolitan nature even then.

Click here to return to the village.