|

The weaving industry in Anglo-Saxon and Viking England was huge, for it's time. Saxon and Viking women, and in all likelihood men, were very skilled at cloth making. Raw flax and wool was spun into yarn, this was then dyed or bleached, woven into cloth and then cut and sewn into the garments their families needed. Socks and gloves were made with nothing more than wood, bone or bronze needle and a ball of yarn. They could even spin very fine silk threads and weave these into decorative braids, although it is more likely that they only ever saw the thread rather than the raw silk fibres. These finer quality fabrics would quite probably have been sold in the markets, especially by specialist producers.

Wool was the main fabric available to the Early Medieval person. This usually arrived in the form of woven cloth, although felt was sometimes made from the raw washed fleece as well. Linen was the next most widely used fibre followed by silk. The silk would have been imported from the east and would have passed through the hands of many traders before reaching these shores thereby making it very expensive.

Linen is made from Flax, a blue flowering plant only 50 cms tall with slender stems that is a member of the Hemp family. When harvested, soaked in water and beaten it can be pulled apart into a mass of stringy fibres. It would then have to go through a further stage of preparation with a tool called a Heckle to separate the fibres and any remaining 'bark', or outer woody stem. The Heckle has a number of long iron spikes set into a wooden block, through which a hank of linen fibres is dragged freeing the linen threads. After some final dressing it is ready for spinning. Yarn from Linen is used to sew shoes together, in sail making and other leather work, although these threads would be heavier and thicker than those used for weaving. The cloth produced from flax is much softer and far more comfortable to wear than woollen cloth. To begin with, the cloth is quite glossy with a waxy sheen to it, but this breaks down over time with washing. It is quite possible that some forms of nettle which are also members of the Hemp family may also have been used in the same way.

|

Wool came from sheep local to the weaver, some breeds giving fine silky fleece, others quite coarse. Fleeces needed to be washed to remove dirt etc from them, and were then 'carded' or combed with a large iron comb-like tool to free the hairs and give them direction so that they could be rolled into sausage like lengths. Often the prepared wool was put on a distaff to make it easier to spin. This is a forked stick around which the carded wool sausages are wound. The distaff is then tucked under the arm and leant on the shoulder, leaving both hands free for spinning.

Having prepared the wool or flax the women (and some men) would then have spun it using a drop spindle (spinning wheels are a much later invention). The spindle was made of wood, or, sometimes bone and was weighted at the bottom with a 'whorl' or UFO shaped weight of clay, wood, bone, stone or metal and even amber. By teasing the fibre out and twirling the spindle quickly the yarn is twisted together producing a thread. The difference in the weight of the whorl, the degree of teasing and the skill of the spinner dictated the quality of the thread. In general terms, the heavier the whorl, the finer the thread, although it increased the risk of the thread breaking. This was not the disaster it first sounds like, as it could always be rejoined to more carded fleece so that you could continue.

After the yarn had been spun it would be dyed using natural dyes. Dyestuffs could have been bought in the market or collected from the countryside. As a point of interest, 70% of all plants in the British Isles will give you a sort of yellow when used as a dye.

The woven threads were wound on a device called a Niddy Noddy or more simply a yarn winder. This enables the dyer to create hanks of yarn that aren't too tightly wound together, ensuring that the dye bath can penetrate all of the fibres and preventing streaking. The yarn would usually be mordanted with oxalic acid from wood sorrel, iron, or even an alkaline solution made from stale urine.

|

The mordanting process enables the yarn to take up and keep the colours in the fibres better. An iron cauldron is all that is needed to mordant with iron or indeed a copper or bronze cauldron for mordanting with copper. Salt helps to enhance some colours and 'hard' water, made hard with chalk if necessary gives brighter colours. Woad leaves with the active chemical indigotin in them were used to give a blue, the process working in the presence of oxygen; the whole of the weld plant for yellow; madder roots for oranges, reds and ruddy colours; alkanet roots for lilac, and the sap-wood from the Brazil tree for reds. The jury is out however as to whether the Brazil tree from Spain was actually used. Even the husks of small beetles called Kermes were used for dying with although it is again a very rare dyestuff in this country. Many other roots, berries, barks and lichens were used on a more localised basis.

Certain colours may have been very regional, but the picture is a very colourful one, rather than muddy and dull. There is a phrase 'dyed in the wool', suggesting that the fleece was dyed before spinning rather than afterwards. However, this might give you a problem dyeing smaller quantities for smaller jobs hinting that the phrase is more appropriate for a more industrialised process.

The yarn was then woven into cloth on a loom. The commonest types of looms were called the warp weighted loom and the two beam loom. The warp weighted loom leant against the wall when it was in use and could be taken apart for easy storage. The warp threads hung down, and were pulled tight by rows of clay loom weights. The two layers of warp threads were held apart by means of a shaft or 'heddle', which could be moved to and fro, thus creating a 'shed' through which the weft could be passed. A single heddle makes a weave known as 'tabby', and by the use of several heddles quite complicated 'twills' and 'herringbone' patterns could be woven.

|

The other type of loom was the two-beam loom, which worked in a similar way to the warp weighted loom, but instead of weights, a bar was used to hold the bottom of the threads taut. Unfortunately it is hard to tell how widespread this type of loom was since it leaves little or no archaeological trace. By the early eleventh century it is likely that professional weavers were using simple, flat treadle looms, although the warp weighted and two beam loom would have continued to be used in the home. Wool and linen could be mixed on a loom, with the wool creating the warp threads and the linen the weft. This combination tangles far less than wool on wool, although an element controlling this is how fine and 'furry' the wool threads were.

Wool fabric could then also be fulled, a process which 'thickened' the cloth with fullers earth. It might have also had its nap raised by the use of teasels over the surface of the fabric. During the actual weaving, tufts of fleece were sometimes knotted into the weave to anchor them, creating a fabric with a hairy or shaggy finish.

The cloth could be 'ironed' by rubbing it between a whale-bone plaque and a large fist sized glass or stone smoother which was heated either in hot sands or by the fire. 'Pleats' could be put into linen garments by twisting them up along their length whilst damp and leaving them somewhere warm to dry. When dried and untwisted the creases gave the effect of masses of small pleats.

There is some suggestion that wax was also used to make the pleats permanent, by ironing it in with the warm glass linen smoothers. This pleating (which may have looked similar to the pleating seen on Fortuny dresses of the early twentieth century) was a fashion of Viking ladies, and has been found in the corroded products on the backs of bronze brooches.

|

Knitting as we recognise it today was not used, although a system of knitting with a single thick needle was known. This technique is known as naalbinding. Continuous loops of yarn are linked together in rows, using a stitch similar to that of blanket stitch. The shaping is done by increasing or reducing the number of loops in a row or by 'laying in' extra rows. There are many different knotting styles that can be used for naalbinding, and it was used mainly to produce gloves, or the feet of socks. The 'legs' of the socks would have been produced using a technique known as sprang. Sprang is a way of weaving that produces textiles with a high degree of elasticity and can be used to weave a tube. A continuous warp thread is set up on a special loom and this is twisted by hand to produce a tight net-like fabric. A thread is passed through the work on completion to stop it unravelling. As well as producing socks, hairnets have been found made from sprang.

Braid was frequently used to decorate clothing and for headbands, belts, hem dressing etc. Most braid was produced by the process known as tablet weaving. Tablet weaving is one of the oldest European textile techniques, traceable to at least the early iron age. The tablets are small flat squares, usually of bone or wood, with a hole in each corner through which a warp thread is passed. The tablets are held in the hand like a pack of cards, parallel to the warp, and turned backwards or forwards by half or quarter turns. This action twists the four warp threads (controlled by each tablet) into a flat pattern that can be locked into position by a weft thread inserted between each of the turns. By varying the colours of the warp yarn and the directions of the turn of the tablets, intricate warp patterns can be obtained. Further decoration can be obtained by 'picking up' a second weft thread, often of gold wire called brocading. Other techniques were also used for braid weaving, although tablet weaving seems to have been the most common.

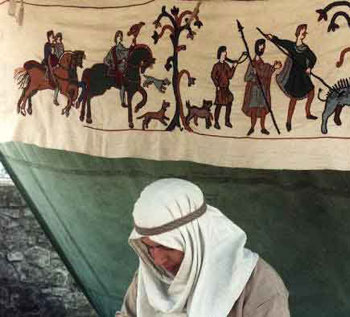

One other area of textile work worthy of note is that of tapestry and embroidery. Amongst the Vikings many wall hangings seem to have been produced using a 'Soumak' technique, as seen in the ninth century Oseberg Tapestry and several twelfth century church tapestries such as the example from Skog church in Sweden. Amongst the Saxons, embroidery seems to have been more popular, both for wall hangings and for decorating clothes. Often the embroidery was made more spectacular by the use of silver and gold threads. Anglo-Saxon embroidery was famous throughout Europe and was often used as gifts on ambassadorial missions.

|

|

|

|

|

Click here to return to the village.